An underwater search for aircraft crash? Sounds awesome. Both José and Simon take on some fascinating personal projects, pushing the boundaries what we do. The real world experience and knowledge directly feeds our training courses and fits into our simple ethos of selling nothing we wouldn’t use ourselves.

One personal project is locating, documenting and researching aircraft lost in the English Channel. Over the past 100 years, many aircraft have vanished, and AccuPixel director Simon Brown has become hooked on finding them.

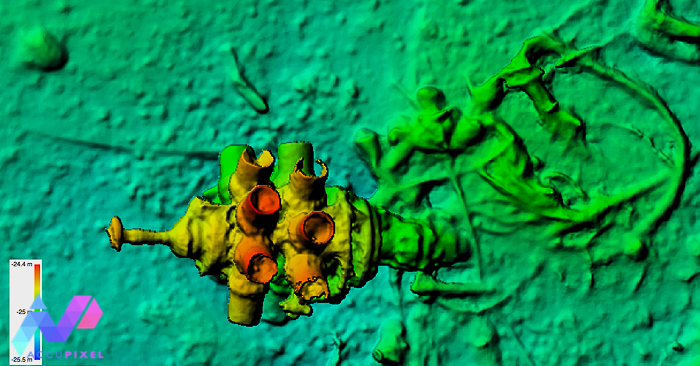

Working with Grahame Knott of Deeper Dorset a few aircraft wrecks have been located over the years. Aircraft crash sites are difficult to locate due to their fragility and susceptibility to trawl damage. Typically, only the heavier components, such as engines, landing gear, and weapons, remain in these underwater searches for aircraft crash sites.

One site typical site is the P47-D Republic Thunderbolt in Weymouth Bay (you can read more about the story here). It has taken 10 years of research to patiently work through the records seeking the pilots name. The hunt through the USAF diaries means we have the names of two potential pilots.

Fisherman’s Snag

The search for another aircraft was triggered by a fishing boat snagging an aircraft propeller in its anchor. We also have a diver’s report of stumbling across an aircraft in the area…all clues point to a crash site.

The fisherman recorded the snag position close to a known wreck. But without an exact location no one really knows if there is an aircraft crash site?

Defined Underwater Search for Aircraft Crash

Knowing where you are underwater is a challenge. When you cannot see more than a few metres in any direction searching becomes difficult. Knowing where you have been, where you are and where to go next is often just guesswork.

However, deploying UWIS and carrying the Alltab by Valtamer running navigation software the diver not only knows where they are, but where they have been and where to go next.

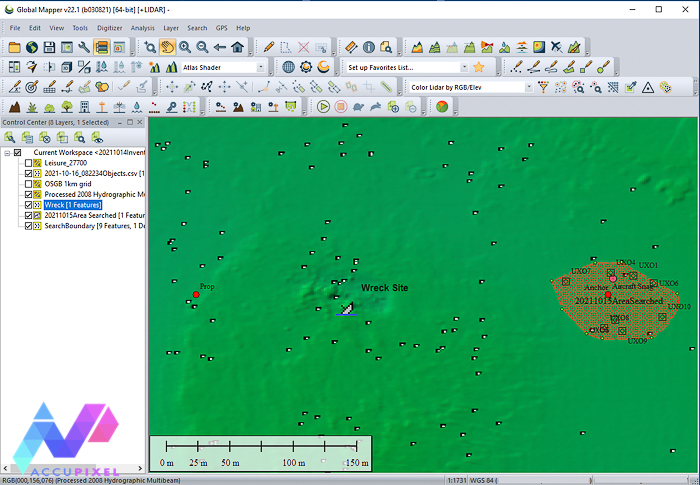

Working outwards from the target the search area was gradually expanded. Quite a few objects looking like unexploded bombs were found and recorded as marks on the Alltab, logging their GPS position for future reference. By marking them we could instantly check whilst underwater to see if we had already visited and made a record, saving time by not investigating the same object twice.

In just under 1 hour of diving, we systematically searched 2,756 square meters of seabed for any sign of an aircraft crash.

Did we find the underwater aircraft crash?

Short answer is “no” but we now know where it isn’t.

By laying out the reported marks, the known shipwreck location and overlaying the UWIS track in Global Mapper GIS software we can define an area as “Searched” and not return. It also helps guide us as to where to look next.

Therefore, we can load boundary of the searched area into the boat chart plotter and make sure we deploy to a new area knowing we are not going over the same ground twice.

We imported the marked objects recorded on the dive as reference for our underwater search for aircraft crash sites. When we add the sonar survey later this year, we will match and eliminate these targets.

The bathymetry overlay we used in Global Mapper is open source and was kindly supplied by Channel Coastal Observatory using their web map service that covers Weymouth Bay.

Efficiency Underwater

Time underwater is precious. Ensuring the diver operates efficiently while searching and recording findings is definitely the way forward for us.

Grahame also appreciated the live view of diver position in the UWIS Tracking software, letting him know where the divers were at all times.

The instant feedback for both diver and skipper is valuable to us. We now wait for another weather window to return and continue the underwater search for the aircraft crash.